Current music:

Qntal - PalästinaliedPlatform: PC

Year: 1989

Developer: New World Computing

The origins of the land

Where does a classic Western role-playing game start? If you were hasteful to say it begins with choosing what role you’re going to play you were somewhat wrong. The same way a theater doesn’t start with raising of the stage curtains but with an usher, a hanger in a cloakroom, and a lobby, RPGs require some kind of presentation before the adventures take off. It must draw a background that created our hero or heroes to be. Nowadays it’s usually done by spectacular videos taking place before any menus, buttons, and other elements of the game mechanics. In 1989, where I want to guide you to, things were different.

Before turning on your computer and running an exe file you had to attentively read a manual. In many cases, it double-purposed as a way of copy protection. Afterall manual consisted not only of brief, comprehensive instruction on gameplay and controls but also included several pages of text about the setting and the preceding events. Without spending time on reading, a person simply had no chance to know what he or she was supposed to do and couldn’t make any meaningful progress in a game.

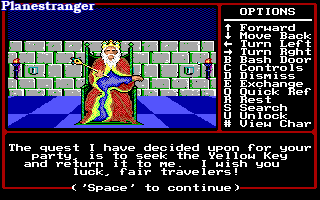

The prologue tells us about Corak the Mysterious, high priest, the most talented mage, and accomplished warrior. Excerpts from his monograph describe the creation of the world from nothingness and a four centuries long war between natural elements that came to life. Migrants from other dimensions started populating the habitat formed as a result of that conflict. The elemental lords, powerful rulers of that world, initially saw no threat in small mortal beings, and when they finally decided to get rid of them, it was too late. They already managed to build cities, taught themselves crafts and magic. Their best minds came up with the artifact that helped the chosen hero to banish the elementals. The hero, named Kalohn, became a king and reigned for a long time until the ruler of the elemental plane of water created the first and the mightiest dragon. Kalohn fell in battle against him. King’s daughter handled the power with less success, while other dragons were growing in numbers. An ecological disaster struck the battlefield. Now there was chaos and decay. The law gave way to brute force. Civilization was balancing on the brink of total collapse.

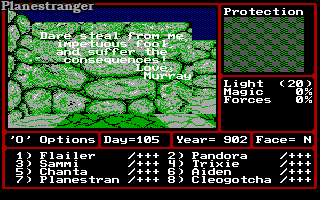

Not so long before the arrival of our team of glory and thrill seekers Corak the Mysterious had vanished. Prior to his disappearance Corak had shared with the trusted apprentice some concerns about the coming of some fugitive wrongdoer from another reality. He also had foretold the champion who could save everybody from the apocalyptic wave of destruction. For the next two weeks, he was locking himself in the library for long hours. Every time he was coming out Corak looked and behaved in some new strange way. After another such vigil, which lasted even longer than usual, he stepped out shouting that he could not prevent the impending end of the world. He then tried to cast an unknown spell and disappeared into a white flash of light. One more week later one of the local lords visited his study. Strange sounds were coming from there, and then it turned out the aristocrat with some of the high priest’s machines had also disappeared. The last element of the mystery that needs to be unraveled was a letter from the missing aristocrat with assurances that everything is fine with him, and an invitation to visit his castle. Now it’s showtime…

Freedom of choice

The ability to take your party from the first game as if you were just continuing the story was marketed as a big feature. However, that’s where we face the usual difference between the promises commercials make and the harsh reality of life. Veterans of past adventures come into the brave new world without any previously acquired equipment. All their stats get the value of 20 while the level is lowered to sixth and age is reversed to raging youth. In fact, all that is left from your feats are names, classes, sexes, and alignments. You can use it as a small bonus to ease the beginning of the game but the difference stops being noticeable as you travel the roads and paths of the area called CRON. Also, I see no reason to limit yourself with what the older version of the role-playing game system had to offer if Gates to Another World has two new playable classes. Though I must beforehand warn all those who aren’t going to stop at reading the review and viewing the screenshots. You should not import a party from the older game even just out of curiosity if you already have newly created characters. All of them with all their long leveling up will be overwritten without a note of warning.

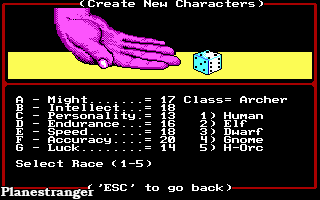

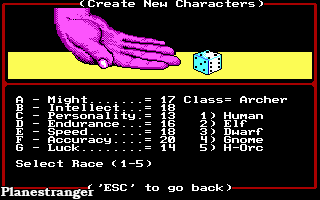

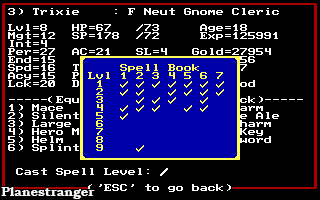

The character generator also speaks in favor of beginning from the scratch. It became friendlier because now it allows swapping stats. Let’s say a player wanted a paladin and got a good set of combat parameters but intellect happened to be higher than personality. He just swaps those two while keeping very lucky numbers on might, speed, and endurance. By the way, classic three dice roll borrowed from Dungeons & Dragons here have added one imaginary side to each dice, so every stat varies from 3 to 21.

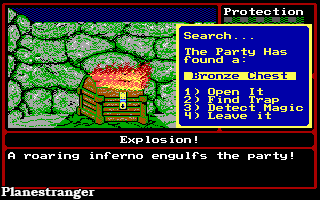

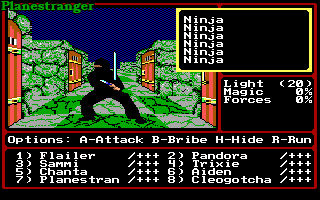

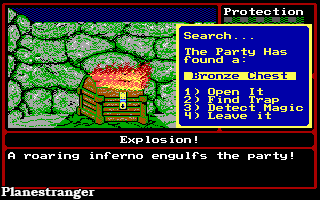

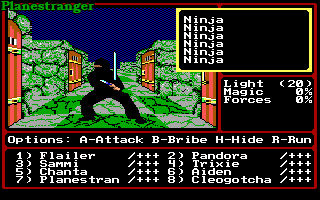

As I said before, ninjas and barbarians have joined the old six classes (knight, paladin, archer, cleric, sorcerer, and robber). The idea with ninjas is clear. You get a robber who devotes more time to melee combat than lock picking and stealth. That class is more problematic at the beginning but it becomes more rewarding later when the skill gap in disarming traps gradually closes. However, I found a bug that allows anybody to safely open chests even with the deadliest protection. As usual, you search for treasures after a successful fight, find a chest, select Find Trap option in the menu but instead of selecting a character who should try to find and disarm a trap you then press Esc on a keyboard. Then again you go with Find Trap and now anybody, even a cleric, for example, can get the contents without any trouble.

On contrary, I’m not sure what good is a barbarian who can’t absorb damage as effectively as a knight due to limitations in armor that class can wear. Having more hitpoints probably plays in barbarians’ favor but it is likely to become a factor near the ending when magical attacks create bigger problems than physical ones. By that time knights and archers greatly surpass them in damage dealt thanks to class unique artifacts.

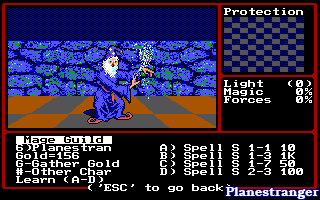

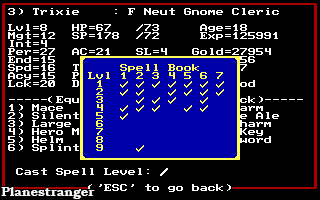

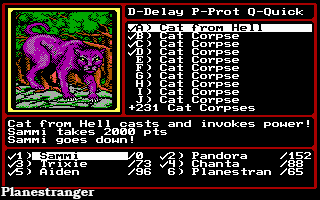

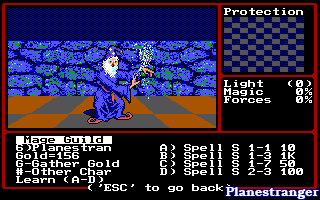

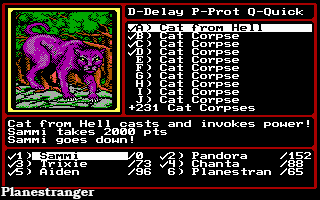

Natural spellcasters start with four spells known to them out of seven on the first level. However, unlike the first “book”, all other magic doesn’t automatically open to clerics and sorcerers with every two levels of a character. They will only get three spells for each level of magic for free. Of course, free stuff is not necessarily the most useful. You’ll have to find everything else in quests or buy from temples and guilds. Mixed classes gain access to supernatural powers in the same way, but with a delay.

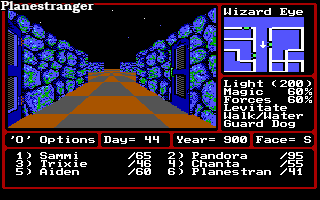

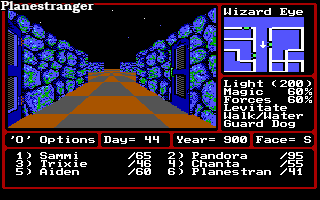

There are nine levels of magic instead of seven now, though each one offers fewer options. All in all total number of usable spells is almost the same. The biggest changes for clerics were the addition of non-combat spells connected to the story and the protection from different types of damage merging into one. Sorcerers have lost several abilities of questionable value like hypnosis or striking fear to their enemies while getting instead additional spells that ease exploration and travel. In particular, here we meet well-known among all the fans of the series Wizard Eye for the first time. Also, they are less restricted in means of dealing the damage. Other classes are limited to the seventh level of magic and below.

There also happened to be a change in gaining hitpoints through the training. In the first game, the number you were getting with each level-up was random. Now it fully depends on the quality of training facilities, one for each town. For example, a barbarian from my party was getting 12 HP per training session in Middlegate, but 19 HP in Atlantium. However, the latter did cost five times more for each visit. Characters don’t age with level-up anymore, though different classes still grow at a different pace. It’s not very noticeable at the beginning but, after the sixth level, the gap becomes apparent with barbarians, knights, robbers, and clerics getting ahead of paladins, archers, ninjas, and sorcerers.

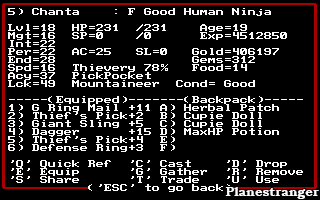

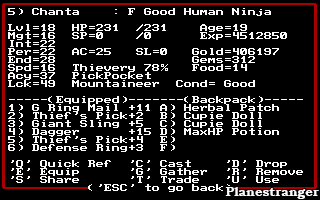

While keeping the foundation, the role-playing system gets more features. In addition to primary parameters, characters can get secondary skills like navigation or cartography. Some of those skills give an unnecessary but nonetheless nice bonus to a single parameter. You can freely choose whatever pleases you more. Some others are immensely important for effective movement through the game world. They also play role in getting and successfully completing quests. It is technically possible to play without them but it will be much more difficult. There are no racial or class-based limits to what skills you can choose. An evil half-orc barbarian may well be a crusader and a feeble gnome sorcerer has all the means to become an athlete. Still, there is no development in skills. You will most likely learn all of them during the first 10% of playtime and then forget about it. The only exception to that is thievery but it is class-related. All ninjas and robbers have it and advance through time without any impact from a player.

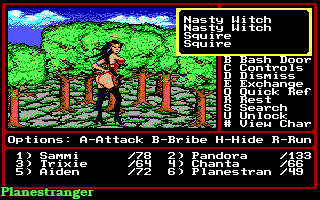

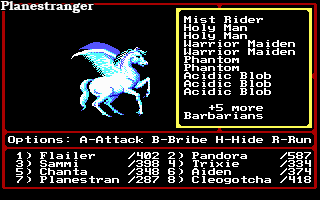

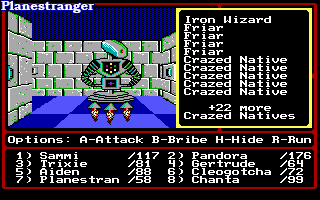

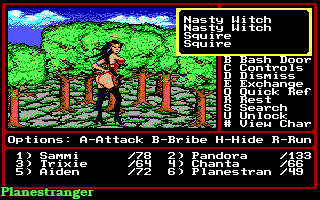

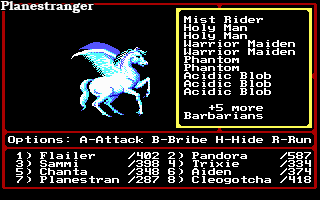

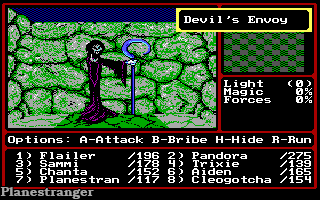

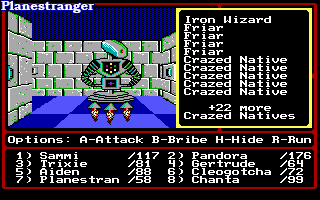

For the first time in Might & Magic series, there are mercenaries whom you can hire to aid your party. They get paid daily based on their level and role in battles (nobody likes to absorb all the damage in the front row). With such hirelings, the maximum number of participants in melee battle on the player’s side can increase from six to eight. It’s worth noting that within this hard limit you can have as many mercantile death dealers as you want. It is even possible to go out on some quest with a team consisting of mercenaries only. However, they will refuse to rest because there won’t be anybody around to pay for the next day of service. So the only rules regarding the party personnel are that you aren’t allowed to have at any moment more than six main characters and more than eight total with the “freelancers”. Hirelings pay for their training themselves. There is also a huge pro for employing magic classes because they know all the spells from the beginning even those they can’t cast yet. Yes, my sagacious friends, even Lloyd’s Beacon and Holy Word.

Alignments don’t cause conflicts among the party members. I noticed that character’s alignment only affected the ability to equip some items and, maybe, slightly changed the probability of different monsters attacking a certain character with all other things being equal. My mixed good and neutral group accepted two evil mercenaries without any objections. Well, they’ve actually never said a word acting as fragments of the player’s own consciousness being split and mixed into the game world rather than as independent agents in the story.

However, equipment restrictions are completely random to the point of idiocy so they give you enough trouble as it is. A neutral paladin may well wear an iron helm enchanted to +3 to armor class. But the very same helm with +5 to AC (including further improvements with the corresponding spell) suddenly comes into a disagreement with character’s values and ideas about good and evil. The more often you find powerful magical weapons you can’t use due to that the more irritation builds up close to the ending.

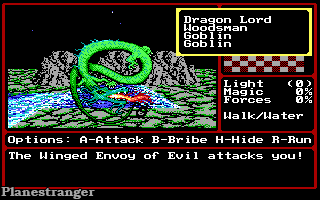

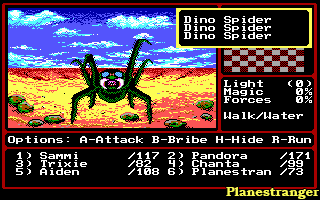

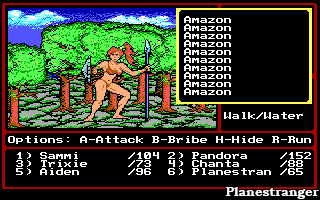

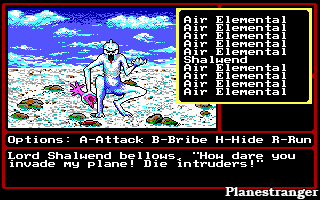

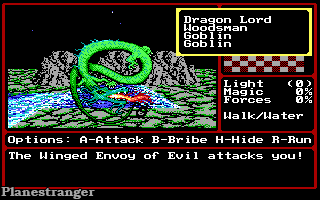

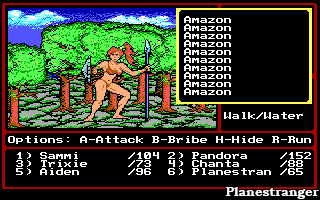

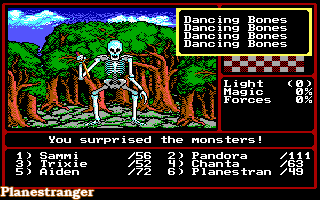

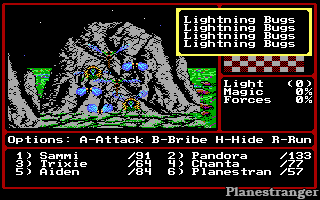

All they that take the sword

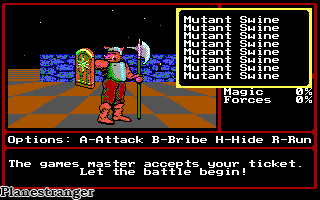

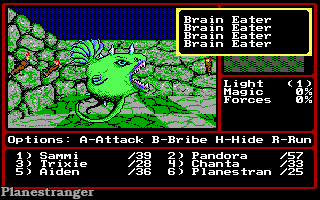

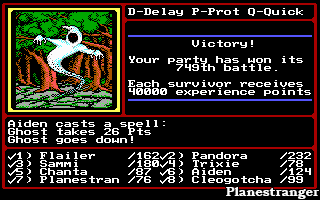

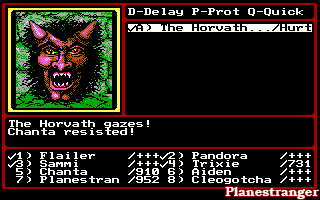

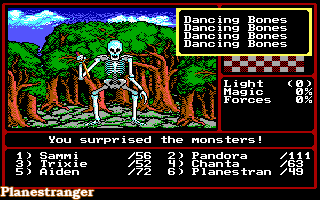

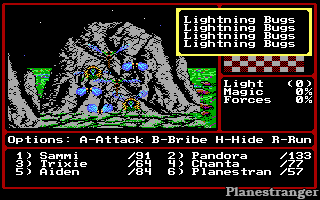

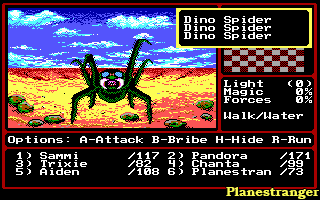

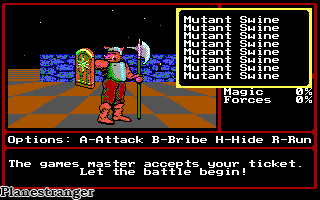

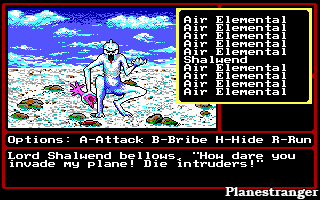

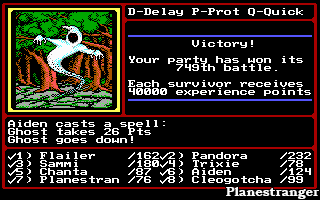

All that may be interesting and all but why does a role-playing game need advanced, deepened game mechanics? To interact with the game world of course. And inevitably for such an ancient RPG battles to the death become the predominant way of interaction with it. The tactical movements of opponents during the combat that were removed in the Macintosh port of the original game are still present in the sequel on PC. Though it is not used as often anymore. Certain monsters can call up reinforcements. The maximum number of opponents in single combat was raised to 250. It does sound impressive, doesn’t it? Well, in reality, this aspect of battles got worse. In Book One, the maximum was just 15 but all the enemies could fight at the same time if not in melee then with ranged weapons and magic from the distance. In Gates to Another World, only the first 10 actually do something meaningful. The rest just stand there and wait for their turn. They can’t attack, use spells, or even run away. That standby reserve is not accessible to heroes under your control. The arrows of the most masterful snipers can’t reach them and even the strongest sorcery of mass destruction unable to harm them. The only positive exception to that is the cleric spell of the highest level, Holy Word, that destroys all the undead creatures no matter where they stand. By the way, there is one inaccuracy with it. Contrary to the game manual the use of this spell does not age a caster.

Now I must go back to the fundamental difference between the statements in a commercial advertisement and the real qualities of a product which open to you only after the purchase was made and the ad had done its job. Here we have a case when you can honestly print an impressive higher number on the cover yet really have a noticeable regression. Besides, such massive fights are just tedious. The whole process of taking out the hoard of some goblins that individually don’t offer any resistance to a minimally adapted party is monotonous. It doesn’t bring new elements to the gameplay. It gives you no new experiences like Might and Magic VI: The Mandate of Heaven did. I had to keep myself from bashing the keyboard in such minutes (seconds are not enough because of everything I have described) without even looking at the screen because my brain was desperately crying for some load to process.

After you leave any area monsters respawn in all squares with fixed encounters even if all the enemies were destroyed. Besides that, if the script didn’t specify the exact numbers and types of monsters, they become stronger depending on your party’s level. Just like that, I was able to explore most of the dungeon beneath the town where adventures begun with first level characters while scattering bloody pieces of wild rats all over and banishing walking skeletons from the world of the living. After leveling up even walking into that dungeon becomes problematic because now I had to face jugglers dealing the damage to the entire party and armed soldiers. So all the crawling around for three days, earning money for quality training seemingly weakens you instead of strengthening. Not the most pleasant outcome. And people were bashing Oblivion…

On the other hand… it helped the game to keep me focused and concentrated when closer to ending I discovered dungeons I previously missed that were more suitable for an inexperienced group. Likely the same thing happened to other players because the world of Might and Magic 2 is truly open from the very beginning. Nobody guides your direction of search nor does someone lead you from easiest targets to progressively more difficult ones. It is completely possible to go where you are not ready to go yet and be ruthlessly destroyed without a word of warning in the first five minutes.

The positioning of enemy groups is extremely sloppy. More so it doesn’t follow the theme of the location. For example, there are barbarians, generic soldiers, and white knights serving as guards inside the castle that greets you with the sign “no humans allowed” and has hordes of undead and demons populating its lower levels. So when you meet creatures that are immune to physical attack in an area where the magic doesn’t work you end up stunned with uncertainty. Was it a glaring mistake or was it sophisticated mockery aiming to prolong the already outstanding gameplay time by a couple of hours? In both cases, it feels bad. Any potential ambiguity disappears when you try to fight your way to treasures through the hardest dungeons only to be stopped by some unknown force when you were already anticipating a sweet loot literally before the last step to it, simply because you have characters of a certain race or class in the party. As a rule, the artifact behind such barrier can only be used by them…

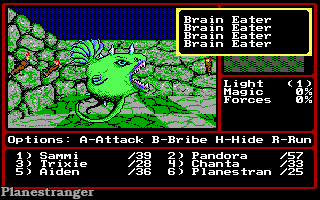

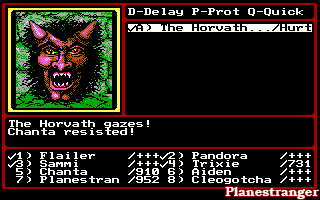

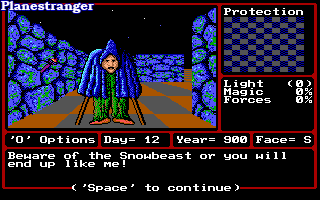

Most of the monsters that inhabit these lands, such as orcs, zombies, or dragons, are well known to anyone even though their special abilities aren’t always obvious. However, you can find few truly original fruits of fantasy, for example, resistant to magic and sleep-inducing brain-eaters, that look very different from either illithids from Dungeons & Dragons bestiary or creatures described by Howard Lovecraft.

The direction of progress

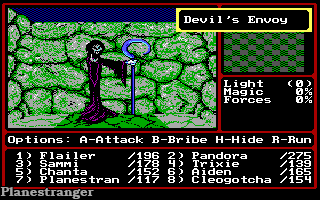

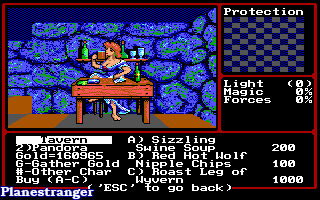

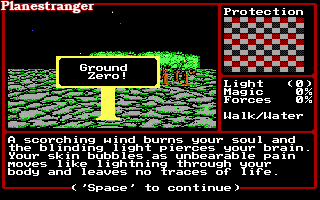

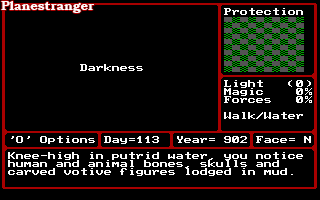

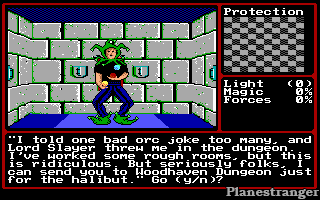

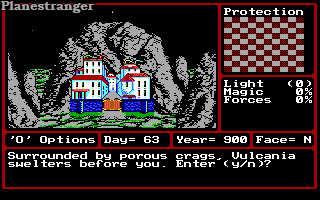

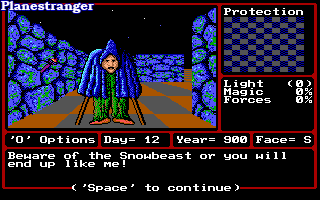

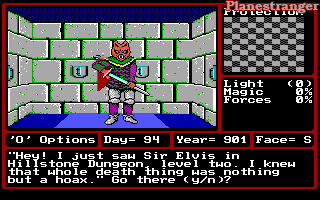

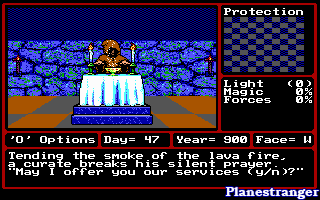

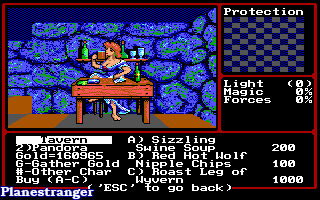

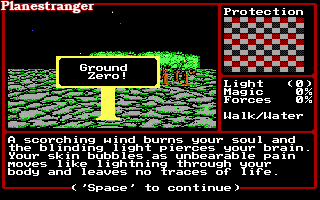

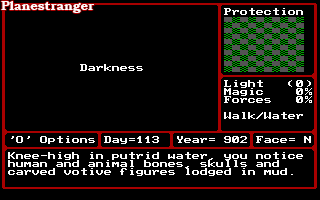

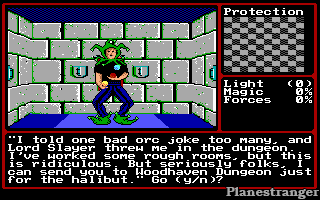

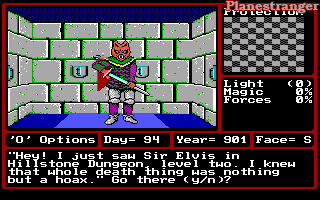

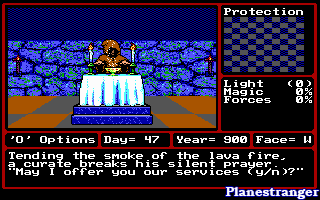

Graphics is where Might and Magic Book Two certainly shines in comparison to the first game. Non-hostile NPCs and services got their own pictures, though not every last one of them. A typical inn owner or a blacksmith has a collective visual image now but unique ones like a travel agent or a neurosurgeon don’t have it. Still, important scenes developing the storyline are presented in text only. There are no animated sequences for that, no static frames even. But the enemies weren’t only naturally placed into the landscape instead of levitating in the black void of the original game, they also were tastefully animated. Although there are still not enough animations for everyone, for example, necromancers and druids look the same. A similar story is with everything else. Walls became nicer and more detailed but every town has the same ones. Both horned devils and chaste maidens in white robes go about their daily business past the same blue stones covered in moss. Unlike the first Might and Magic, the graphics weren’t just copied from the technologically obsolete Apple II platform that saw the release a year earlier but were redrawn to use the entire available color palette of EGA video cards.

There is just one visual blooper. In a castle, while taking a walk through long corridors you can see the sky changing colors according to a current time of day. To me, it feels a bit weirder than the possibility to encounter a mounted patrol in said corridors.

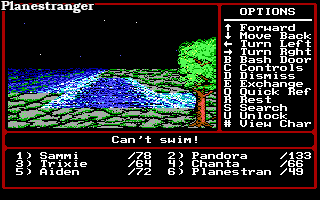

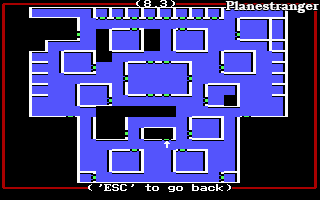

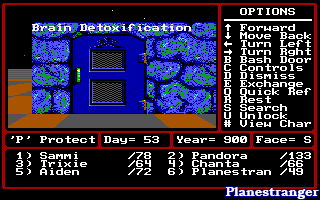

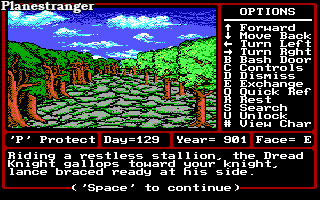

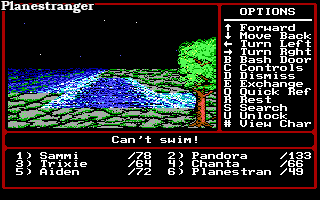

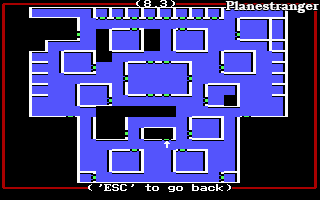

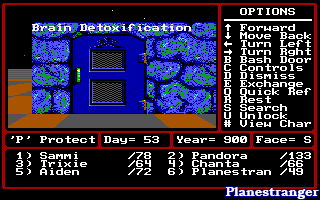

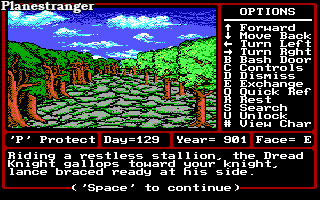

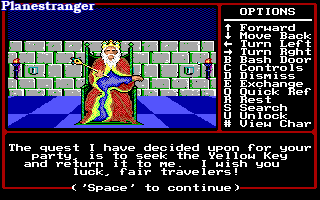

Noticeable yet less consistent progress towards comfort was made in user interface and control mechanics. For instance, the options screen not only allows to choose the speed of in-game text or to turn sounds off or on but also to set the frequency of random encounters. However, the most important new feature I want to thank developers for is automapping that turns on with learning the secondary skill of cartography. The map appears by simply pressing the M key and works even in pitch-black darkness where you can‘t see normally. It’s hard to understand to those who’ve never had the experience of navigating sterile minimalistic labyrinths where one passage is indistinguishable from neighboring ones. If you missed the opportunity to play something like that you’ll have to believe my words. It felt nothing lesser than a revolution comparable to first analog sticks on gamepads or hardware-accelerated texture filtering on 3D objects.

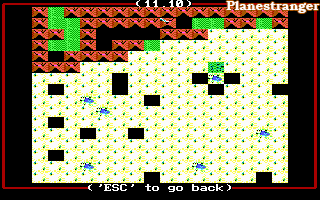

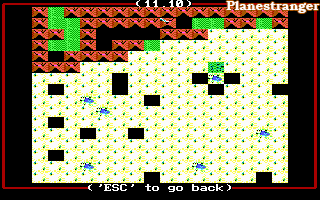

Nevertheless moving through the desert is a tricky task even with cartography and navigation skills because the white arrow that marks your current position and the direction you’re facing is not visible in yellowish-white sand. So you’ll have to use the old-fashioned mastery of orienteering with only coordinates at hands.

Ecumene consists of the same 20 sectors seamlessly sewn together. All of them are 16×16 squares and each field may contain something of interest. Comparing to the previous game the bigger part of adventures takes place in towns, castles, multi-level caverns, and other unsafe places giving players 36 more squares to explore. Add to that elemental planes and travel in some strange mix of time and space, when well-known places reveal new properties, and it becomes a truly huge world which can take you 200-250 hours to honestly complete without guides and cheats.

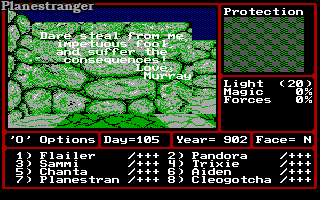

It would be too good to be true without one particularly annoying thing. Sometimes in order to see some messages including important ones related to the main questline you must not only be present on a specific tile but also be facing a certain direction. Because of that I spent quite a lot of time revisiting the locations I had already explored.

The game map wraps on both axes. In other words, if you come from some point and keep going straight in one direction you’ll get back to the same spot. Though the logic of the world seemingly was finished before the addition of that feature and would fit a simple rectangle with hard borders better. Due to that if your group moves from the easternmost part of the land to the east it will immediately turn up on the westernmost part jumping from icy wasteland to hot desert in one step.

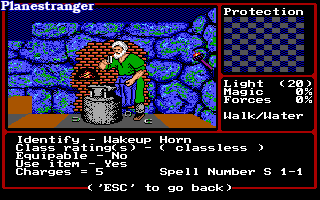

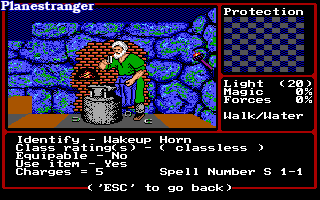

Cluebook is not the sole source of knowledge about the parameters of acquired weapons and armor anymore. An expert at the blacksmith for a good coin will describe not only the goods they have for sale but also magical artifacts, potions, and robber tools. It’s expensive and inconvenient but nevertheless, it’s an important improvement. Speaking of shops, there is nothing easier than selling a key quest item. That happened to me by accident once.

There was a constant lack of space in the inventory. Every character, as in the first game, is able to equip up to six items and six more can be stored in the backpack. So, at the first glance, you notice the maximum number of free slots increased from 36 to 48 but the same happened to the quantity of miscellaneous objects that potentially come in handy who knows where. Therefore your routine trips back to towns in order to sell accumulated loot happen more often. You can’t just give up on income and throw stuff off because at no stage of the game money will stop mattering. In the beginning the price of training that doubles in a couple of level-ups scares. Then it becomes clear that the mercenaries’ cost is many times higher. Even with a “salary cap” at 50000 gold per day for a single worker in the field of pain and destruction the expenses can become problematic with no attention to money. And there are other, less obvious, but no less financially demanding ways to spend the riches.

In combat, in a variety of catacombs full of traps, or outside in the wilderness, where snowstorms, earthquakes, and boiling lava can harm you, the health of the entire party is displayed at all times. For that developers had to sacrifice the length of names. The Secret of the Inner Sanctum did fit my nickname on the screen while the sequel didn’t.

However, the more you comprehend the depth and variety that the world of CRON offers, which was at the time one of the most complex and detailed, the more lack of any information about changes happening around annoys you. The status of each character at any given moment is defined by 24 variables. If you take a drink from some magical spring or touch some unidentified object these variables can change. But the game won’t tell you which ones precisely, by what amount, and for how long. Perhaps Van Caneghem himself was keeping pieces of paper with sets of characters’ parameters close to the keyboard as he was accustomed to since playing tabletop D&D and tracked the changes by comparing them to what was currently on the screen. I had to just take screenshots of the character status screen where all the numbers are displayed, before and after the interaction, and look for the differences. Though even that approach doesn’t work well in all situations. And neither of two seems convenient to me, so it only adds up some dull routine to the already long list of chores like manual mapping, recording all the information, memorizing spells and properties of items.

The sound is the technology that remained in its infancy in Might and Magic Book Two. There is no music except the one you hear on the title screen and that’s a pity. Wandering through ancient minimalistic catacombs becomes so much more memorable when the soundtrack resonates with your mood. Phantasy Star can confirm. Outside of encounters, there is absolutely nothing to hear except short repetitive sounds of movement to another field and collision with a solid barrier. Next to that, even the poor short loops that indicate victory in a battle or finding loot aren’t that terribly jarring. Having at least something is better than complete auditory deprivation. Also, the adequate saving feature is still missing. You can only save stats and inventories of characters in each of five inns.

Distinctive features

Here nobody forces the storyline on you. Heroes under the player’s control never say a word. You won’t get into a situation for which you’ve never had a model of behavior in your head, like meeting an old githzerai lady who begs for a merciful kill. Might and Magic 2 doesn’t offer anything outside of well-known mass culture tropes. Nevertheless, when people speak about Gates to Another World being too focused on battle tactics they oversimplify it. At least the numbers of non-playable characters, puzzles, quest objects have increased since the original game as has the amount of text.

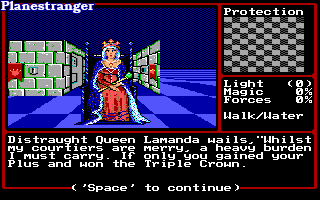

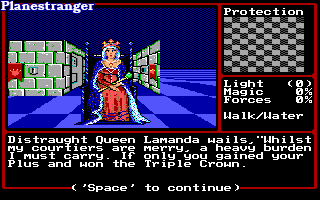

It simply uses other tools to immerse one into the experience than people would have expected in five years after the release, not to mention in thirty-plus years. The whole thing works thanks to the open world that is there for you to discover, to look for something interesting to do in on your own. It is really an outstanding feeling that by touching the keyboard you actually have a world at the fingertips when you found the clue to start the quest yourself, when you were thinking about the solution and finally found it without any help. No high-budget, professionally written, voiced by Hollywood actors, and looking like the best examples of cinematography scene between the walks where you’re led by the hand from point A to point B can give that. Might and Magic II would be boring to watch in a stream, but a player who is ready to get carried away and who won’t give up when facing difficulties will be rewarded. Princess Lamanda and the person with not quite obvious gender identity who happened to be an apprentice of the character that ties both “books” together are more memorable than carefully modeled and animated companions from AAA action that you finished in one evening despite having no voice acting and not taking part in a theatrical act of Chekhovian magnitude.

There are relatively many side quests though in terms of depth and variety they have little to amaze you. Most of them are solved in one action. Kill the monster! So you kill it. Find an object! You go and find it exterminating various fauna specimen on the way. Puzzles elevate this straightforward concept. Somewhere you stumble upon the information about the very existence of a puzzle. It doesn’t happen automatically because there is no journal or some formal invitation “Quest received! Accept? Yes / No” as RPGs back then didn’t have those. Then during the mapping of the territory, you bump into the solution or a hint that leads to the solution. Finally, after some thought process, you come up with an idea of where and how to use it. It happens naturally. Data comes to you the same way it does when you notice tiny bits of changes in the reality around, clues, motivations, and reasons to act on the way home from a daily job or to a grocery. It is entirely a player’s choice to react on them or not. Few quests, such as making a donation in all the temples or tasting each and every meal in the world, also unobtrusively strengthen the motivation to discover new facets of Cron.

I can’t avoid giving special recognition to cryptographic brain teasers. For those who have no idea how far we’ve gone mentally from the 80s, or, due to annoying ads of Fortnite, League of Legends, or indistinguishable mobile entertainment apps, perceive computer games as something objectionable and idle that generally leads to intellectual degradation and is predominantly appealing to young fragile minds, I will give an example without naming specific details and throwing obvious spoilers. During the adventure, you pass by a meaningless, seemingly incoherent sequence of symbols. It is expected that at some point you will notice them and make a decision that it’s not just part of the scenery, but something important. Most likely that will happen when you encounter another similar inscription, and another one, and one more… Then you begin to purposefully look for them guessing to put it all together into a single text block that looks like a randomly mixed set of letters and punctuation marks. Desperate attempts to recall university lectures on cryptography and try to find some simple cipher like Caesar’s shift last for hours and bring no result, because at no stage does it become known to you how many parts there are, and whether you have seen all of them. Later another piece accidentally comes across. Cerebral convolutions struggle with the problem again. Something begins to loom but the whole picture doesn’t come together despite all the efforts. Again you find a fragment and again you meditate on the letters until your eyes hurt. Eureka! After the cipher is defeated the genuine message vaguely explains about some dude who lives seclusively in his hut somewhere in the wasteland. He, it says, will give a hint. And with that hint, you go to such and such unusual pool, and it will be awesome… if you then pass the test. It, of course, doesn’t specify where the named pool is located. Got it? All that trouble was to just get a hint where to get a hint in order to pass the test who knows where.

With the current market shaped by DLCs, loot boxes casino and gameplay mechanics where “pay to win” model has defeated “press X to win” model for good, nobody has to overcome such difficulties even for easter eggs. While here it was quite naturally built into the gameplay and became the essential part of the whole experience that is required to reach the good ending. The game shows no intention to adapt to any paying customer and accept his skill level, no matter how inept and dense he may be. On the contrary, it challenges the player, dares him to overcome hard obstacles, and, as a result, makes him more skillful than before. Moreover, success can’t be achieved by perseverance and mindless grinding alone, you have to actually strain the neurons of the brain.

It’s still possible to repeat most of the quests an unlimited number of times, collecting experience and treasures to no end. And while the combat ones maintain some balance, the fact that the whole party can repeatedly receive rewards for a once solved riddle inflicts a devastating blow to it. I found a way to gain experience points indefinitely without obstacles and complications when my group was as low as eighth level. And if you take into account there are leprechauns who randomly destroy items, including unique ones that are critical to the storyline, it becomes obvious that the need to repeat some missions was an intentional decision. So if Van Caneghem was aware that people would replay some of the quests why didn’t he think about the disbalance that other could create? This point seems to me to be a clear mistake in game design.

The need to change the party roster along the way was an unorthodox decision by New World Computing that had turned into a really professional team that used more than ten people to create the PC version. In Secret of the Inner Sanctum you could theoretically change the set of characters for each playing session but why would you do that if a balanced group that gets all the experience is more effective? But now there are unique promotion quests for every class that don’t allow others on board during the completion.

I desperately tried to avoid splitting the party but it turned out that class-specific quests were necessary to complete the game and there was no way around it. And even after that, there was no alternative to breaking the well-knit team in accordance with the storyline at least one more time. As if it weren’t the heroes on a mission to save the world but simply a bunch of random thrill-seekers hanging out in a tavern and occasionally, in different combinations, making forays for the next artifact or someone’s head as a mean of personal enrichment. This doesn’t help to immerse into the story and, although it bears a closer resemblance to the life we all know, the roleplaying element, the feeling of being in other reality suffers from this. What’s good for Jagged Alliance and X-COM is not welcomed in the universe of might and magic.

A bit of light humor has been added for the sake of variety and to liven up the world. For example, in the house of the very first quest giver, there is a locked room called skeleton closet. You will never guess what could be found there. And in the depths of one of the toughest dungeons, an NPC says he doesn’t believe in death of lord Elvis. The game doesn’t shy away from a little trolling. The residents’ committee of Atlantium offers to send you to Middlegate just for 25 gold in order to keep the town beautiful.

I would like to point out the sloppiness of the chronology as one of the lore’s shortcomings. The history of the world with the development of civilization, the emergence of towns, and other epoch-making leaps like that in less than a century seem to be dated so solely for the convenience of balancing mathematical formulas in which aging and bad ending after the deadline are possible.

Total sum

The main advantage of Might and Magic 2: Gates to Another World is that despite all the mentioned difficulties I’ve never felt that typical resentment and dull hopelessness which quite often go hand-in-hand with rogue-like games. For those titles, a random world seed that is theoretically impossible to beat may be a completely trivial thing. Well, you just die, get reborn, repeat, not a big deal. Aum in every field and let’s keep the samsara wheel spinning after the reincarnation. Gates to Another World is different. The hand of demiurge can be felt in every small detail, and the proportion of mental sticks and carrots was selected in such a way that the difficulty of monsters and puzzles doesn’t outweigh the desire to see what lies beyond the next turn of castle catacombs. It works so well that even the obviously tipped balance of variables of this realm didn’t turn out to be fatal to the gameplay. Here and there you get small bonuses like an unexpected reward for efforts or a little joke. As a result, the main goal for a long, challenging game is achieved. You never lose faith in your own ability to complete it.

When you solve a riddle on your own, when you level up and finally defeat that scary beast which you had met long before and which, without any chances, had kept sweeping away the whole group in a single round, you really feel on top of this artificial world where only your will matters. In this sense, the silent figurines consisting of abstract numbers merge into a truly multifaceted, complex personality that possesses an undoubted agency and therefore is alive – your own.

Summing up, it can be said with confidence that it is here, where the characteristic features of the series began to appear: mercenaries, special skills of the characters, battles with endless hordes of fantasy creatures at once, the world which is as open to exploration as possible without anybody leading the player on a leash along the predetermined route. It’s clear that Van Caneghem was no longer engaging in a retelling of the founders of the genre, Ultima and Wizardry, but instead began to experiment with his ideas which would later lead the series to its peak.

Altogether, this was a big bold step forward but, like with a toddler who has not yet fully learned to walk, the direction of movement did not quite meet the desired course and a foot landing on a solid surface was not yet able to reliably hold the entire body weight which is why it was waving and tilting dangerously in search for stability. Much of the way to a user-friendly, well-thought, and polished interface that wouldn’t pose a challenge to overcome in addition to enemies was still ahead. And many of described shortcomings don’t allow me to rate the game higher, even though so far this is the strongest candidate for the title of the best RPG from the 80s of all that I’ve played.

Rating: 6.5

Читать независимый обзор игры Might and Magic Book Two: Gates to another World по-русски